Horatio Nelson 1758-1798 AD

One of my favorite naval commanders to sail the seas, and the greatest Brit to ever do it. Shoutout all my one eyed ballers out there.

1. Some Baller Instances

Have you ever heard the phrase “Turn a blind eye”? Well if you have, thank Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte KB. Nelson was blind in one eye from an incident early in his career which allowed for the famous saying that he spoke at the battle of Copenhagen in 1801.

Nelson was an officer at the time of the battle, and he commanded the HMS Elephant. The fleet was under the command of the paranoid and cautious Admiral Sir Hyde Parker. Sir Hyde Parker signaled to Nelson as he began his attack aboard the HMS Elephant. He commanded Nelson to pull back from his attack.

When Nelson was informed of this by his flag commander he raised his telescope to his blind eye, faced Sir Hyde Parker’s ship, and remarked something along the lines of “I haven’t the slightest idea what he’s trying to say” and promptly ordered his ship and some nearby vessels into a frontal assault.

Nelson’s ballsy attack was incredibly successful, leading to a decisive British victory in large part due to Horatio Nelson’s maneuver. After this, the disgraced Admiral Sir Hyde Parker was relieved of duty for his timidity. Command of the fleet was then bestowed to the hands of Horatio Nelson.

Nelson “turning a blind eye” to Sir Hyde Parker’s command to hold his advance

When Napoleon scored a massive victory against the Mamluks in Egypt during the summer of 1798, he threw lavish celebrations Cairo. He boasted about his exploits and taunted the “pathetic” British who were helpless to stop him. Napoleon’s plans of far eastern conquest were becoming realized and the British hopes of stopping French world domination were waning.

But Horatio Nelson hadn’t heard no bell. “Victory is not a name strong enough for such a scene” (modern-day translation: why you celebrating bro?) retorted Horatio Nelson said when he heard of Napoleon's flamboyance.

Nelson then proceeded to destroy Napoleon’s entire fleet of transports, supply ships, and warships which were anchored in Alexandria. This turned Napoleon’s army from being an unstoppable force to a totally stranded unstoppable force.

Extra unfortunately for Napoleon, the Mamluks were technically under the protection of the Ottoman Empire, who then declared a holy war on Napoleon and completely annihilated his army with Napoleon himself barely escaping - the campaign was a decisive French defeat. All because my dawg, Horatio Nelson, cut Napoleon’s line of retreat.

2. Background Check

Horatio Nelson was born in Burnham Thorpe, Great Britain on September 29th, 1758. His father was named Edmund Nelson, a somewhat notable priest. Horatio Nelson joined the Navy via the influence of his uncle, who was a high-ranking officer in the Royal Navy.

Nelson’s exceptional performance as a naval officer propelled him through the ranks, where he soon found himself commanding several small battles near Toulon. Later, the young Nelson first distinguished himself during a decisive victory in the British invasion of French-held Corsica, in which he played a pivotal role. However, Nelson sustained an eye injury during the battle - eventually leading to him losing sight in it fully.

Nelson fought in fifteen battles, of which thirteen were against Napoleon’s combined force of Spanish and French navies across the wars of the First, Second, and Third Coalition. He was victorious in eight out of the thirteen battles against Napoleon and wounded in action four times.

Now, eight victories out of thirteen battles is nothing legendary on its own. However, the last of his eight victories, the battle of Trafalgar, is.

3. Trying to Beat Napoleon (Attempt 3/7)

Some context: a few years after the end of the War of the Second Coalition, the British had refused French demands to leave Malta and Egypt. This prompted Napoleon to begin assembling a large army to invade Great Britain in order to re-assert French dominance in Europe.

However, there is one issue that everyone who has ever tried to invade England has faced. Great Britain is an island. Unlike the rest of Europe, Napoleon could not just simply march his army there and destroy Great Britain in the same manner he had erased the rest of his European foes.

In order to invade England, Napoleon would need a fleet, a very very big fleet to transport his troops; and so, he commanded one be built - and so it was.

In response to Napoleon raising new armies the British began blockading French imports, leading to the outbreak of the War of the Third Coalition. Although Napoleon's exploits on land were unmatched, Great Britain still maintained an advantage in naval technology and crew ability.

Due to Napoleon not expecting a renewal of hostilities so soon, his navy was dispersed far and wide in harbors throughout his empire.

The British quickly moved and blockaded French ports with their superior numbers where Napoleon’s ships were stationed. This neutralized Napoleon’s whole navy except for 9 ships of the line that were stationed in the Atlantic.

In a stroke of luck for the French, the British sank a couple of Spanish vessels, maybe on accident, maybe on purpose, provoking the Spanish navy to join the conflict. Napoleon now had the numbers he needed to break the British blockade.

The British blockade around the port of Toulon was particularly loose and French Admiral Villeneuve managed to escape with twelve ships of the line and join forces with the Atlantic contingent. After some raiding, Villeneuve’s contingent met with the Spanish navy at the port of Cadiz.

Villeneuve was ordered by Napoleon to move his fleet to Italy, which Villeneuve disregarded, opting to stay at Cadiz. A few weeks later he received another letter from Napoleon, instructing him to stay in Cadiz until his replacement arrived.

Villeneuve again ignored this order and set out to sea, but Nelson was waiting, near the straits of Gibraltar, the battle of Trafalgar was about to begin.

4. Pre-Game

On the morning of October 21st, 1805, Villeneuve was woken to the spotting of British vessels on the horizon. Impressed with the strength of the British force, Villeneuve ordered a withdrawal back to Cadiz.

However, Nelson had intentionally waited a full day before engaging his enemy in order to maximize their distance from Cadiz. Making retreat very difficult - especially for Villeneuve’s ill-trained crews; their maneuvering was clumsy and inefficient. They were unable to retreat before Nelson closed the distance, Villeneuve was left with no choice but to fight.

Now there is one thing you must understand about naval warfare at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. It was traditional that each side would form one long line parallel facing the opposite direction of the line of the enemy (hence the name “ships of the line”) and they would just exchange broadsides with one another as they passed.

This strategy was primarily utilized due to the ease at which orders could be relayed throughout the line via flag. These battles were often fairly inconclusive and had relatively low casualties on both sides due to fast communication making it easy to perform an orderly retreat.

But, Horatio Nelson, who had just recently been placed in command of the whole British Navy, didn’t seek an inconclusive skirmish but rather a decisive battle. So instead of ordering his ships to mirror the numerically superior Franco-Spanish navy’s line formation; he instead arrayed his fleet into two columns oriented head-on towards the Franco-Spanish fleet, intending to use his ships as hammers to shatter the long, but thin line of his enemies.

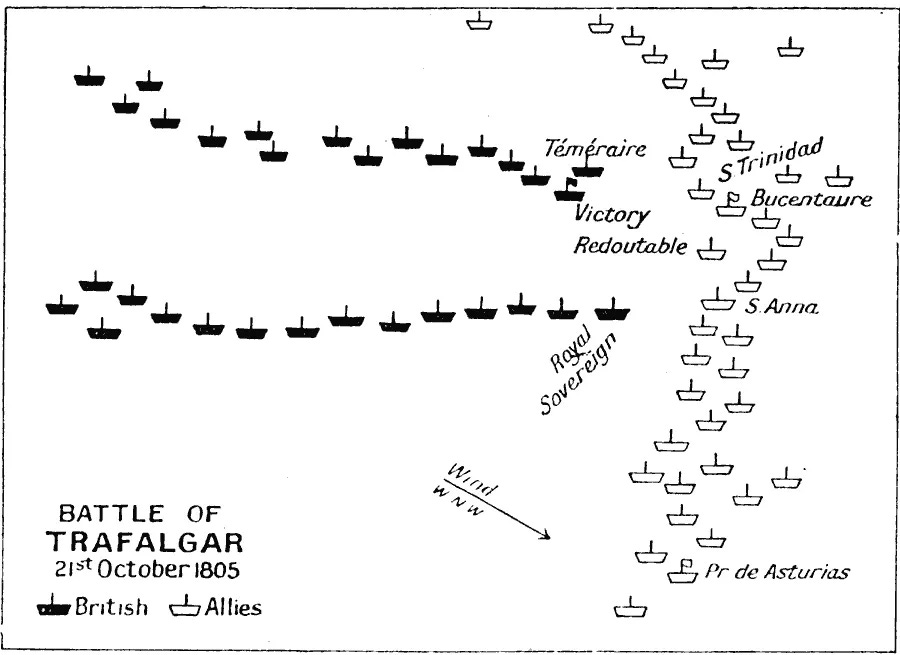

For those who lack imagination, a picture is below. Please keep note that Nelson fielded 27 ships of the line whereas Villeneuve commanded 33.

Depiction of Nelson’s (black) unorthodox ship deployment against the French/Spanish (white)

Arraying your ships like this has a few advantages for Nelson: First, ramming through the thin line of Franco-Spanish ships would cut off lines of sight, disrupting their communications. Nelson especially made an effort to isolate the enemy flagship, and source of orders to the rest of the fleet, the Bucentaure.

If he could force each ship to engage in chaotic one-on-one battles instead of the orderly line battles they were used to, Nelson believed that his veteran loaders and gunners held the advantage compared to their inexperienced counterparts and would be able to win the day.

Secondly, attacking head-on closed the distance as fast as possible between the two fleets, preventing a Franco-Spanish retreat back to Cadiz.

However, there was one drawback to Nelson’s plan. While the British fleet approached head-on, the Franco-Spanish fleet, who were oriented in a line perpendicular to Nelson, would be able to hammer broadsides into the approaching ships; and the British wouldn't be able to shoot back.

Nonetheless, Nelson took the gamble, he knew that Villeneuve’s gunner crews were inexperienced. This led him to conclude that they would have difficulties firing on the fast-moving British ships approaching them in an unorthodox fashion. He assumed correctly.

5. Trafalgar

“England expects that every man will do his duty”, was Horatio Nelson’s famous command that ordered the beginning of the Battle of Trafalgar. The quote is still commonly addressed to British crews by commanders to this day before battle. Nelson personally led the northernmost of the two columns from the front aboard his flagship HMS Victory.

The British southern column, led by Cutberth Collingsworth, aboard the HMS Royal Sovereign, attacked first. Although they sustained some damage on their initial approach, they soon came crashing through the frail southern end of the Franco-Spanish column.

Britain's experienced crews began ripping volley after volley on both sides. Collingsworth’s ships strategically pierced in between two ships so they could unleash both of their broadsides at the same time, ripping the enemy ships apart before they could even turn from their traditional line formation to face them.

Horatio Nelson began his attack soon after with his Northern column, targeting the center of Villeneuve’s formation. However, the wind was unfavorable, and they became slow-moving targets, easy picking for enemy cannons. But Nelson and his men persevered.

As they got close and enemy fire got more intense, Nelson ordered a turn. It appeared to the French and Spanish that Nelson had enough of the unrelenting hail of cannonballs and was ordering his contingent to form a line for a proper battle. But this was just a ruse by Nelson.

Just as it appeared that Nelson’s group had formed an orderly line, he suddenly ordered a hard turn back into their original hammer formation. The wind had changed and was with the Brits, there was no stopping them now. Nelson and his column smashed straight through the Franco-Spanish line. Aboard the HMS Victory, Nelson had engaged in ferocious fighting with Villeneuve’s flagship the Bucentaure.

Both ships took lots of damage and Nelson was wounded by a French sharpshooter in the mayhem. But eventually, after orders to reinforce the Bucentaure went unnoticed—due to Nelson’s planned chaos—the HMS Victory gained the advantage over the Bucentaure, who eventually surrendered. With the Franco-Spanish flagship neutralized, communication halted along the fragile Franco-Spanish line.

Chaos began to ensue, and the battle basically devolved into a bar fight with boats. Unfortunately for Villeneuve, Nelson’s men were like a biker gang of boats. Their experience and fighting capabilities are comparable only to that of veteran Waffle House night shift employees. Whereas his men were closer in fighting ability to that of those annoying malnourished tiny sausage dogs that just bark at you. They don’t even bite or anything, just annoying yap every second you're around them.

The southern end of the Franco-Spanish column was suffering greatly from the overwhelming power of the British double broadsides. The surrender of the Bucentaure, paired with the sinking/crippling of many allied ships in the center enticed the entire southern line of the Franco-Spanish fleet to surrender.

They had gotten the worst of the British assault. The remaining Northern portion of the Franco-Spanish fleet had moved into position to assault Nelson’s northern column, but seeing the devastation being incurred by the British, they lost heart and retreated.

6. Britannia Rules the Waves

The British victory was absolute. The British lost zero ships but took 1,666 casualties. However, they captured eighteen ships of the line (out of a total of thirty-three present) from the Franco-Spanish fleet and sank one, which is close to 60% of the ships for the entire allied fleet.

The Allies took close to 7,000 casualties with another 7,000-8,000 men taken prisoner. Nelson’s men crushed their croissant-loving counterparts in a way never before seen in Napoleonic naval warfare.

By far the most notable loss for the British was the death of Admiral Horatio Nelson himself. The shot he received from the French sharpshooter turned out to be fatal. He lived to the end of the battle, after he heard the news of the extirpating victory, he gave thanks to the Lord saying “Thank God I have done my duty” and then promptly died 15 minutes later. Nelson’s surgeon heard him mumble his last words “God and my Country”. He died at half-past four, Nelson was 47 years old.

Depiction of Horatio Nelson’s heroic death after the Battle of Trafalgar

The impact of the Battle of Trafalgar cannot be overstated. It ensured British naval domination for the next century to come, eradicating basically every naval asset of the French and Spanish. Almost as importantly it crushed any of Napoleon's dreams to invade England, something he would never end up doing — all thanks to Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte KB.

Horatio Nelson is also remembered for his policy and ideals regarding the controversial topic at the time: slavery. If Nelson’s ship were to find itself in the company of runaway slaves, they would be offered clemency in exchange for paid service aboard the vessel, rather than turning them in for a reward which was custom at the time.

The runaways would be cared for the same as the other sailors and after they had completed their duty, they would be set free and given the same awards for their service as the European sailors.

Nelson’s body was preserved in a barrel of brandy and sent back to England for a proper funeral. He is commonly remembered as the Greatest British naval officer ever. His bold strategies and baller one-liners gave him a legacy that no one can turn a blind eye to.