Hannibal Barca "The Greatest Threat Rome Ever Knew" 247 BC

Among the most superb battle tacticians to ever walk the planet, Hannibal Barca gave Rome a scare it would never forget when he crossed the Alps in 218 BC...

Hannibal Barca 247 BC

I will begin by noting that Hannibal Barca is my favorite general of all time, and quite frankly nobody else comes close. I hope to persuade some of you to see as I do.

1. Context

There once was a mighty empire, a beacon of wealth and commerce, a hub of cultural exchange, a center of innovation, and an empire whose dominance in the Mediterranean Sea was unmatched by any at the time. This jewel of the Mediterranean was known as the Carthaginian Empire. Their economy flourished due to the uncontested trade of African and Iberian goods throughout the Mediterranean. Carthage, located in modern-day Tunisia, was the capital of this mighty empire that controlled the seas from the Strait of Gibraltar to Sicily. The inhabitants became wealthy and life in Carthage flourished, until 264 BC when the First Punic War broke out between the mighty Carthaginian Empire and the stubborn, newly established, Roman Republic.

In an act of perseverance, sheer strength, and display of the indomitable human spirit, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians in a shocking victory. The Romans took most of Sicily and the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, enabling them to compete with Carthage for dominance in the Mediterranean, deeply hurting Carthaginian pride. One of the few successful Carthaginian commanders in this war was named Hamilcar Barca. He fought a successful guerilla war in Sicily, perhaps the only successful facet of the entire Carthaginian war effort. Hamilcar was disgraced when he learned that the weak Carthaginian senate had surrendered to the Romans and when he returned home he held a strong grudge against the tenacious invaders, one which he would pass onto his son, the greatest threat Rome will ever know, Hannibal Barca.

Hannibal was born into the Barcid Dynasty in 247 BC in Carthage. He was provided a superb education but much like his father, what he truly excelled at was military warfare and tactics. Hannibal grew up despising the Romans, vowing to re-assert Carthage’s dominance in the Mediterranean when he grew of age.

He distinguished himself as an excellent general during the Barcid conquest of Hispania, which saw the Carthaginian Empire conquer many territories in Iberia shortly after the First Punic War. Hannibal waited patiently until 218 BC when he began his journey to honor the vow he made to avenge the Carthaginian defeat in the First Punic War.

2. Hannibal Crosses The Alps & Smashes Romans

It began when the general of the Carthaginian Army, Hasdrubal the Fair was assassinated and Hannibal was elected the new commander of the Carthaginian Army. After he shored up some disputes in Iberia he set off towards Rome in great haste. However, one problem presented itself, the Alps. The Alps are a massive mountain range in Northern Italy, an extremely hostile climate, especially for an army, and especially for elephants. This was Hannibal’s first test, and he passed with flying colors. He formed an alliance with a Gallic tribe knowledgeable in the routes to Rome through the Alps after serving as a judge in a dispute between the king and his subordinates. Pleased with his work, they provided him with guides and supplies. Hannibal then proceeded to do something that history will never forget. He marched his 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 40 war elephants across the Alps. Yes, 40 Elephants across the Alps. He accomplished this in just 15 days, which was completely unprecedented for any army of any size.

However, his journey was not without trial. He had many skirmishes and small-scale battles with local tribes attempting to raid his baggage train along the way. He was often ambushed because the tribal knowledge of the Alps gave them an advantage. But Hannibal and his army persevered. Once Hannibal reached the Po Valley he set up camp and waited eagerly for a Roman target.

Hannibal’s sudden appearance out of the Alps in late November sent shockwaves throughout Rome; the senate thought it impossible for Hannibal to cross the Alps in that short of a time before the winter started, hence they had already sent their armies to winter quarters. The senate then hastily recalled their consular armies and ordered them to march on his position.

Shortly after arriving in Cisalpine Gaul, Hannibal scored his first victory against a Roman cavalry contingent at Ticinus. Although the actual battle was fairly small and insignificant it displayed Hannibal’s ability to defeat the Romans; and soon enough Gallic tribesmen, who hated the Romans, started pouring in from every corner of the Po Valley, bolstering Hannibal’s ranks to around 35,000-40,000 soldiers. But the first test of Roman resolve lay ahead of him, at Trebia where Roman Consul Sempronius Longus waited eagerly for Hannibal with an army 40,000 strong - 36,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry (regrettably 0 elephants because his army is from Italy).

Sempronius Longus was one of two Roman consuls that Rome elected that year. Rome’s government was quite interesting: they would elect two new consuls each year and utilize many checks and balances to ensure that no one man gained too much power. However, this had the unintentional side effect that the consuls had only one year to earn as much fame and glory as they could, leading many to go on foolish conquests so that they would be remembered.

Speaking of glory and fame, Sempronius Longus was eager to get some. However, his army was newly raised and quite inexperienced compared to the Iberian and Libyan veterans Hannibal wielded in his army. Longus was urged by the other Consul, Publius Scipio not to engage Hannibal in a pitched battle; for Scipio had been the victim of Hannibal’s exploits at Ticinus. Longus however, sought the praise of those back in Rome, so he promptly moved to attack Hannibal’s army. Longus set up his camp on the other side of the river from Hannibal's camp. That night, while Longus told his men to rest, Hannibal set his trap.

At dawn on the snowy morning of December 22nd (or 23rd it isn't known for sure) the Romans woke up to a startling surprise. Hannibal’s elite Numidian cavalry was launching projectiles over the camp palisade and into the camp. Hurriedly, and on empty stomachs, the Romans prepared for battle. When the Romans left camp Hannibal’s cavalry wheeled about and headed back for the riverbank and forded the river back to Hannibal’s side. Longus ordered his men to follow the Numidians across the river. Chest-deep in the freezing cold river the Romans pushed on, only to be met with the lines of Hannibal’s army waiting for them on the other side of the riverbank.

Hannibal arrayed his well-rested and well-fed army as so: veteran Libyan and Iberian infantry flanking the sides of his bare-chested Gallic allies. He placed his war elephants on the flanks of the Iberian and Libyan infantry who he then flanked with his cavalry. Longus arrayed his heavily armored Roman Legionaries in the center flanked by lighter allied infantry flanked by cavalry. Longus held a slight numerical advantage.

Longus ordered a charge, his center saw success as the well-armored Legionaries hacked through the bare-chested Gauls. However, Hannibal’s cunning proved to be far more valuable than the toughest of steel. The night before the battle, Hannibal had carefully surveyed the battlefield and located a dry riverbed out of view from the Romans, where he hid 2,000 of his best men led by Hannibal’s brother, Mago Barca. Just as the Romans thought they had gained the upper hand, out came Mago and his grizzled veterans behind the Roman lines. Their timing was perfect: just as they appeared, Hannibal’s cavalry managed to rout Longus’s cavalry, who were protecting the Roman flanks. Then the full force of Mago’s troops, combined with the Carthaginian cavalry, smashed into both of the Roman flanks, shattering them instantly.

Seeing this disaster unfold, Longus himself crossed the river and abandoned his men as he fled to safety. Now all that remained were the legionaries in the center who maintained an orderly retreat towards the nearby city of Placentia. Roman casualties were estimated at 28,000. Whereas, Hannibal suffered between 3,000-5,000 casualties; his most notable loss being almost all of his elephants, perhaps all but one. A decisive Carthaginian victory nonetheless.

Panic ensued in the Roman senate as they rushed to find a solution to deal with Hannibal. The loss of Roman prestige at Trebia persuaded many more Gallic tribes to ally themselves with Hannibal and soon Hannibal’s ranks surged to around 50,000. Other Gallic tribes also began conducting their own operations against the Romans contributing to the chaos, such as the Boii who slaughtered a 25,000-strong Roman army on its way to re-assert Roman dominance in Cisalpine Gaul - the Boii left 10 survivors of the 25,000 to tell the story. Even though Trebia was far from the most decisive victory Hannibal would enact on the Romans, it was the springboard that gave his army the momentum it needed for the following years of campaigning.

In the following years, Hannibal enacted numerous defeats on the Romans at Victumulae, Lake Trasimene (saw the destruction of an entire Roman army with 25,000 dead, including its consul), Ager Falernus, Geronium, Tarentum, Capua, Silarus, Herdonia (twice), Numistro, Canusium, Petelia, and Crotone.

These embarrassments were the context the senate needed to do something monumental, they raised the largest army ever in Roman history. Around 85,000 men - mostly infantry - were raised from all corners of the empire. They trained over the winter and marched to meet Hannibal, their morale high because of their unprecedented numerical strength.

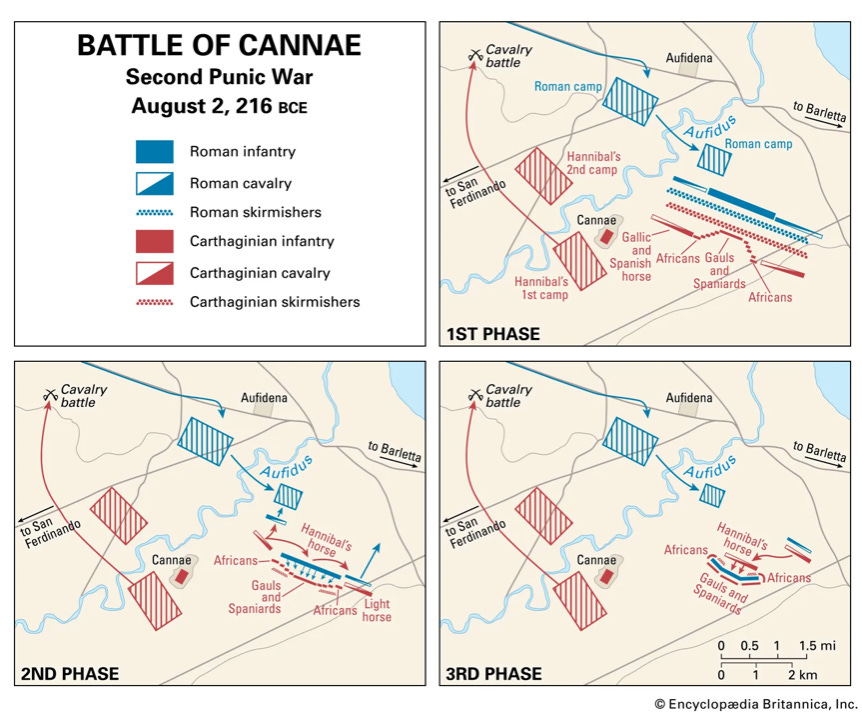

They met Hannibal at Cannae, where Hannibal was preparing to do the unthinkable. Now for a little heart-to-heart, seeing as I have already gone very in-depth about the battle of Trebia, I will save you the boredom of reading about yet another battle; instead, I will provide an image because we live in a digital world I guess. Please note that Hannibal has a total of 50,000 men versus the Roman 86,400.

To sum it up, Hannibal ridiculously managed to hide infantry on an open field. He did this by using his skirmishers to kick up lots of dust to conceal the position of 6,000 handpicked elite infantry. Once the Roman blob of infantry had pushed too far they lost cohesion due to their overconfidence. It was then that Hannibal sprung his trap. His most elite Libyan infantry charged out from behind the dust straight onto both of the unsuspecting Roman flanks, now the Romans were fighting on three sides! But it got worse, just as the momentum turned in favor of Hannibal, the Numidian and Spanish cavalry appeared behind the Roman army after they had routed the numerically inferior Roman cavalry. They attacked the last remaining non-engaged side of the Roman blob, simultaneously cutting off the Roman line of retreat - something very scary if you were a soldier. The Romans were hemmed in on all four sides, and at that point, it was just like stealing candy from a baby for the veteran Carthaginians. Hannibal squeezed the Romans in tighter, so tight that in some parts of the makeshift circle, Roman soldiers didn’t even have enough space to raise their weapons to defend themselves. Some tribunes tried to make small clumps of resistance, a few thousand men strong, but they too were eventually stomped out. It was a massacre of sinful proportions. Rome lost anywhere from 67,500 - 80,000 men. Whereas the Carthaginians lost close to 6,000. It’s incredibly difficult to put into words how masterful this victory was. It was the most decisive defeat Rome would know for centuries, some would say ever. It was so bad that it was used as a benchmark in future Roman defeats. After battles, commanders would convene and ask one another “On a scale of mama mia to MAMA MIA how decisive was that defeat?” (MAMA MIA being equivalent to the Roman defeat at Cannae). After the battle of Cannae, it is estimated that up to that point, Hannibal had killed 25% of all Roman men aged 18-50.

All this and the Romans had yet to enact one defeat against Hannibal. He was completely and utterly unstoppable. The only strategy that served the Romans well against Hannibal was known as the Fabian strategy; created by Consul Fabius Maximus. The doctrine stated that no matter what, do not fight Hannibal under any circumstance. Sometimes Fabius would just sit and watch other Roman armies get eviscerated by Hannibal from behind his walled cities and palisaded camps, but he would refuse to help and risk his own annihilation. Instead, he would just watch in sadness.

The Fabian Strategy outraged the senate and general populace along with damaging Roman prestige, this caused many defections in Southern Italy to the Carthaginian cause, most notably the city of Capua and its surrounding region. However, Hannibal thought the strategy to be quite genius. Considering that Hannibal was away from Africa he lacked a secure supply chain, ergo he had to live off the land. Fabius knew this and attempted to prevent Hannibal from supplying his army through the use of edicts ordering that Roman farms be burned and livestock killed to prevent Hannibal from taking the supplies for his army. This forced Hannibal to dispatch his brother Mago to the Carthaginian senate to request reinforcements and supplies via the sea.

3. Carthage’s Shortcomings & Rome’s Greatness

Now at this point, you’re asking the same question I did when I first heard this story: How in the world does the Carthaginian war effort get stopped if Hannibal is seeing unrivaled domination in Italy? A spectacular question my young Hannibal lovers and I will give it to you plainly. Every other commander and politician in the Carthaginian Empire sucked. Like really sucked. And those stubborn Romans just didn’t know when to quit.

Firstly, the Carthaginian politicians were greedy and refused to send meaningful reinforcements to Hannibal because they were worried that he would become too powerful. Instead, they opted to send Hannibal’s much-needed 20,000 reinforcements to Iberia where Hasdrubal, Hannibal’s brother, was losing ground to a pair of Roman commanders named the Scipio brothers. They also dispatched a 12,000-strong contingent to Sardinia to support an uprising against the Romans led by Hasdrubal the Bald (different guy) where the Carthaginians were decisively defeated at the battle of Decimomannu.

But you might be asking yourself, if Hannibal is scoring all of these victories, why does he need reinforcements? Doesn’t it make more sense to send the reinforcements to the theaters of war that are less successful? That was exactly the point stressed by Carthaginian Aristocrat Hanno II to the Carthaginian senate in a successful attempt to divert more of Hannibal’s reinforcements to Hasdrubal in order to defend Iberia, Iberia conveniently being the place where all of Hanno’s land holdings were. To answer your question, Hannibal’s army was tired after many years of campaigning away from home. They needed fresh troops to shore up their irreplaceable losses from all of their battles and to raise morale. Also, if Hannibal had received adequate reinforcements he could have had sufficient numbers to march on and besiege Rome itself; something that his army was unprepared to do without the proper engineers, resources, and numbers. If he captured Rome that would very likely end the war on the spot in the favor of Carthage, something that seemed impossible to do otherwise. The decision not to send Hannibal reinforcements was greedy and selfish on the part of the Senate and was one of the main factors that led to Carthage’s ultimate demise.

But, as much as I love Hannibal and want to blame his eventual defeat solely on his enemies in the senate, unfortunately, this is not so; And I wouldn’t be doing history justice if I didn’t talk about the largest reason Hannibal wasn't victorious. The Romans.

In my opinion, there is no time in history that people have been tested greater than the Romans during the first and second Punic wars. In the first Punic War, they lost close to 200,000 men to the sea alone. But still, they persisted. In the second Punic War, they lost a quarter of their fighting population to Hannibal’s martial prowess. But still, they persisted. Hannibal ravaged the Italian countryside for 15 straight years, causing massive devastation to the civilian population and the economy. The people begged for surrender. But still, they persisted. The effect that this had on the Carthaginians was evident on the battlefield and back home. It seemed to everyone that no matter what Hannibal did, the Romans simplywouldn't give up, they wouldn’t even consider a peace treaty which is astonishing considering what happened at Cannae. This demoralized Hannibal’s troops and fueled the frustration of many senators at home, who blamed Hannibal for being incapable of finishing the war. For the rest of his life Hannibal would think to himself, of every civilization that has ever existed, why have the gods led me to fight Rome.

At this point Hannibal’s supply situation was dire, if he did not receive reinforcements and supplies soon he would be forced to withdraw to Africa. However, there was good news. Hasdrubal, Hannibal’s brother, had just appeared out of the Alps. He came from Iberia, with an army of 35,000 strong with the intention of meeting up with Hannibal’s army in south Italy. The Romans could ill afford this reunion; if this were to happen the war would surely be won in favor of the Carthaginians. But it was not meant to be. Roman Consul Claudius Nero (not THE Nero) managed to deceive Hannibal, seeing as Hannibal was unaware that his brother's army had made it through the Alps. Claudius managed to make it appear to Hannibal that he, as well as his full Roman army, were still encamped near Capua. But in reality, he and his army stealthily withdrew and made way to meet up with the other consular army to fight Hasdrubal in the North.

Hasdrubal was decisively defeated at the battle of Metaraus where he died, along with 10,000 of his men, and 5,000 more were captured. Another contingent 21,000 strong led by Hannibal’s brother Mago intending to reinforce Hannibal was also decisively defeated at the battle of Insubria. Hannibal was on his own.

Eventually the Romans, in line with the Fabian strategy, just abandoned efforts to rid Hannibal of the Italian peninsula and just invaded Africa instead. With the walls of Rome garrisoned and Hannibal's supply situation in perilous condition, the senate made the decision to recall him and his veterans to Africa to defend Carthage. The Carthaginians had lost their initiative.

Now to introduce Rome’s saving grace, Publius Cornelius Scipio, later known simply as Scipio Africanus. He was the son of the previously mentioned consul Scipio who was defeated at Ticinus, the first engagement of the war. Regardless of being just 19, Scipio was present as a tribune at the battle of Cannae and was one of the lucky survivors who most likely managed to fight their way out of Hannibal’s encirclement. Although he was defeated at Cannae, he was surprisingly assigned as a general to the war in Spain where he performed excellently, so excellently that his troops declared him king. Scipio rejected this honor as to avoid the wrath of the senate but the message was clear, Scipio was that guy. After winning the consulship in a landslide (even though he was ineligible to hold the office for many reasons) he was assigned as governor of Sicily. He then asked the senate if, as governor of Sicily he would have the authority to launch an invasion of North Africa. The senate was like ‘nah’ because they were scared of Scipio gaining too much power. But, then Scipio was like ‘Well I might just do it anyway’ so then the senate stripped him of all of his legions and was like ‘You and what army’? To which Scipio responded by making a volunteer only task-force that quickly grew to 7,000 men, most of whom were veterans. which wasn’t enough to invade Carthage but was enough to freak out the senate and they ended up giving Scipio back all his legions with permission to invade North Africa.

4. Final Defeat

Hannibal’s army was confronted by Scipio, soon to be Africanus and 29,000 legionaries on the plains of Zama outside the city of Carthage. Hannibal marshaled 36,000 infantry, 1/3 of whom were citizen levies (poor quality), another 1/3 were Spanish mercenaries (decent quality), and the final 1/3 were veterans from his campaigns in Italy (remarkable quality); he was also supplemented by 4,000 cavalry and 80 war elephants. However, in an impressive diplomatic feat, Scipio managed to sway the Numidians, one of Carthage’s African allies, to change allegiances and support them in the battle. They brought with them 6,000 elite Numidian cavalry, something that would be crucial to the outcome of the battle.

Before the battle commenced it is said that Hannibal and Scipio met face to face accompanied only by a single translator. Hannibal sued for peace, “It was I who first began this war against the Roman people. And though I seemed so often to have victory in my grasp, fate has willed it that I should also be the first to seek for peace. I come of my own free will, and I am glad that it is you from whom I seek it; there is no one I would rather ask it of. I am glad, too, that it will not be the least of your many great achievements that it was you that Hannibal surrendered to, who had claimed so many victories over Rome’s other generals, and that it was you that brought an end to a war made famous by your countrymen’s defeats before my own. This is indeed one of Fortuna’s richest jokes that I first took up arms when your father was consul, I fought against him first of all Rome’s generals, and now without my arms I am here to seek peace terms from his son.” But Scipio was having none of it, he could do little more than laugh at the conditions Hannibal proposed, highlighting how Hannibal was “contriving to leave out of [Hannibal’s] current proposals anything in the terms of the original agreement that was not already in [Rome’s] possession [at the start of the war]”. Scipio finished by stating that “Therefore, if you have anything you wish to add to the peace conditions previously proposed, as compensation perhaps for the losses to our ships and their supplies which you destroyed during the armistice, and for the violence done to our ambassadors, then I will have something to take back to our authorities. But if that is too much for you, prepare for war, since peace you clearly find intolerable.”1 How Livy knew what they said when this event took place over 150 years before he was born and there was apparently only one witness, I do not know. But, it’s pretty sick nonetheless.

Hannibal arrayed his elephants in the front and the cavalry on his flanks, followed by his infantry in three lines: the first line was the mercenaries, the second was the citizen levies, and the third and final line was his veterans. This final line of Hannibal’s infantry on their own may be the most experienced/effective group of soldiers in all of history, they had fought for 16 consecutive years and were 14-0 against the Romans in the field. The battle began abruptly as half of Hannibal’s elephants, who weren’t fully trained, charged out straight towards the enemy line before they were supposed to. As they were charging, for some unknown reason, the elephants turned left, and then left again, and then left one more time and slammed straight into their own Carthaginian left flank. Hannibal could do little more than a facepalm before he sent his remaining 40 elephants forward in an attempt to disrupt the Roman lines.

But, Scipio had a plan. Instead of arranging his army in the standard Roman checkerboard formation, against which elephants were very effective, he arrayed them in vertical lines with space in between them. This is genius because although elephants can be trained, they can’t be trained to be suicidal. Provided the options of either running into a vertical line of Roman men or running through an uncontested lane in between them, they’ll choose running through the gap every time. So, all 40 of Hannibal’s elephants ran straight through empty space instead of into Roman lines. The elephants were then killed by projectiles and spears from the Roman soldiers on either side of them. In the end, Hannibal’s elephants did more harm to himself than to Scipio.

Next, Scipio’s cavalry charged and were quickly able to rout Hannibal’s cavalry from the field. Now all that was left was the infantry. Hannibal sent his first two lines of mercenaries and citizen levies forward and an intense melee combat began in the center. After a while, the mercenaries grew tired and turned to flee only to be met by the spears of the Carthaginian citizen levies behind them, which encouraged them to turn back around and keep fighting. But, after hours of fighting the citizens and mercenaries were finally routed from the field. Hannibal’s first two lines put up a good fight and the Roman army was reduced to only about half of its men at fighting strength. Rome’s army was tired and Hannibal’s final line, his best line, hadn’t even broken a sweat. A few minutes passed before Hannibal gave the order. His dreaded veterans advanced. At this point the Romans were beginning to think that this was Hannibal’s plan all along; their hope was quickly fading. Hannibal’s men charged into the Roman line, hacking down legionaries by the hundreds, their momentum carrying them forward. For this brief moment, Hannibal could breathe easy, Carthage had been saved. The Romans had been pushed to the breaking point, it was only a matter of time until his veterans pulled through, he could see the Roman line faltering, he could hear their cries for help, he could taste the victory in the air, he could see the Roman cavalry charging in from behind. Wait? The Roman cavalry charging in from behind? Oh dear. And just like that, Scipio had pulled a Hannibal on THE Hannibal. After a long pursuit, the Roman cavalry realized that the Carthaginian cavalry was just trying to lead them away from the battle, so they turned around and after a long ride back, slammed into Hannibal’s rear. At that point the battle was lost, but Hannibal’s soldiers were still a formidable force, and they still put up staunch resistance. But, it was clear to everybody the battle was over.

After the battle, Scipio approached Hannibal and Livy records their conversation as follows: “When Africanus asked who, in Hannibal’s opinion, was the greatest general, Hannibal named Alexander… as to whom he would rank second, Hannibal selected Pyrrhus… asking whom Hannibal considered third, he named himself without hesitation. Then Scipio broke into a laugh and said, ‘What would you say if you had defeated me?’”2 I think Hannibal was fair to put Alexander at #1 but Pyrrhus at #2 is simply laughable. Hannibal was clearly better than Pyrrhus and some could argue better than Alexander. But, that is a discussion for a different day.

Carthage sued for peace; the Romans' terms were very harsh. Carthage ceded all overseas territories and some African territories to the Romans, including all of Spain. The Carthaginians were required to pay 10,000 talents over 50 years and many hostages were taken. Rome also demanded that the Carthaginian fleet at no time exceed 10 warships and they were forbidden from waging war outside of Africa. Even in Africa, they had to ask Rome’s permission before going to war. There was no question, Carthage was under the absolute authority of Rome.

Although the ultimate Carthaginian war effort was a failure, Hannibal was in my opinion the greatest threat Rome ever knew; greater than Atilla and his Huns and greater than the Shapur I and the Sassanids in the East. The battle of Cannae sent Rome to the verge of capitulation and if it hadn’t been for Carthaginian incompetence and greed elsewhere, paired with never-failing Roman resilience, the Second Punic War undoubtedly would have been a smashing Carthaginian victory. Hannibal’s unrivaled ability to set traps and brilliant utilization of cavalry paired with his unwavering resolve is what makes him my favorite general of all time. He was so unstoppable in open battles that the Romans were forced to just watch him ravage their territories, unable to stop him without themselves falling prey to his cunning. Also, who doesn’t love a guy who marched elephants across one of the largest mountain ranges in the world?

Your honor, I rest my case.

Whether or not you’ve come to love Hannibal or believe he was doomed from the start, there is something to be learned from his story. The biggest lesson comes neither from Hannibal’s brilliant victories nor the burgeoning Republic’s unyielding tenacity. Rather, from one of the less flashy figures, the Carthaginian Senate. When I first heard Hannibal’s story I couldn’t help but be angry at them for failing to support Hannibal when he needed it most. This reminded me of something that I was told by one of my mentors, no matter if you hate someone or disagree with their plan, by refusing to support their idea in earnest, you are dooming it to fail. This mentality is seen on steroids in the aristocrat Hanno II; he was so resentful of Hannibal’s power and consumed by his greed that he refused to send Hannibal the reinforcements he so desperately needed, resulting in catastrophic failures in other theaters of war, and eventually the fall of Carthage itself.

Don’t be a Hanno II. Even if you don't like someone else’s plan, do what you can to help it, because you may be the key to making it work.

Have a wonderful day,

Gideon.

Livy, “Chapters 28-37” (Rome), Book 30.

Livy, “Chapter 14” (Rome), Book 35.